Tackle a big, topical, contemporary issue in a film and you’ll find that making a statement can sometimes come at the expense of telling a good story. There should never be a fine line between a movie and public service announcement. They are two distinct forms and we should know which is which. Thankfully Promised Land director Gus Van Sant and stars/co-writers Matt Damon and John Krasinski keep things balanced for the most part.

Based on a story by Dave Eggers, Damon plays Steve Butler, an affable, confident representative of a natural gas company. He arrives in a small Pennsylvania town and, after a stop at the local general store to pick up a regular guy wardrobe, he sets out to dazzle the cash-strapped residents with big money to let his company drill on their land. The problem is that, in case we don’t know by now, we surely learn from this movie that drilling for natural gas involves a controversial processing called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking as it is commonly known. While everyone in town needs the money, there are a significant number of residents, led by a wily high school science teacher played by Hal Holbrook, who are against the prospect of creating a devastating environmental disaster.

Butler is a pro through and through and ready to pull out all the stops. It has been said that politics really just boils down to a couple of people talking in a room and talking to people is what Steve does best. He seems up to any challenge but when Dustin Noble (Krasinski), a scruffy grassroots environmental activist who is twice as charming and affable as Steve arrives in town to organize the fight against the gas company, he finds himself on shaky ground for the first time in his career.

Yes, Promised Land threatens to get more than a little preachy now and then. Damon, Krasinski, Holbrook and Frances McDormand as Steve’s colleague Sue all get showy moments and monologues as the film examines the topic. Even though it threatens to go over the top, the film never gets heavy-handed.

One of the big challenges of this film involves asking the audience to get behind and root for the guy we all know is the enemy. It is a little hard to not recall Bill Forsyth’s wonderful, magical Local Hero, which involves a representative of a Texas oil giant trying to buy out the residents of coastal Scottish town and ending up charmed by them. Thanks to a nifty narrative curveball, we wind up seeing Steve Butler in a new light. Overall, Promised Land is a solid, understated film but, for all of its indie credibility and earthy-crunchy politics, the biggest surprise is its unfortunate Hollywood ending.

This review originally appeared on cinedelphia.com:

http://cinedelphia.com/promised-land-review

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Fading Away

Years ago, a radio consultant did a demographic study and determined that people, especially men, always tend to go back to the music they listened to between the ages of sixteen and twenty. It makes some sense. At that age, we are no longer kids; we have most of the autonomy and few of the responsibilities of adults. We might be running around with our friends and experiencing first love with a pulsating, raucous soundtrack. Who wouldn’t be nostalgic for that music?

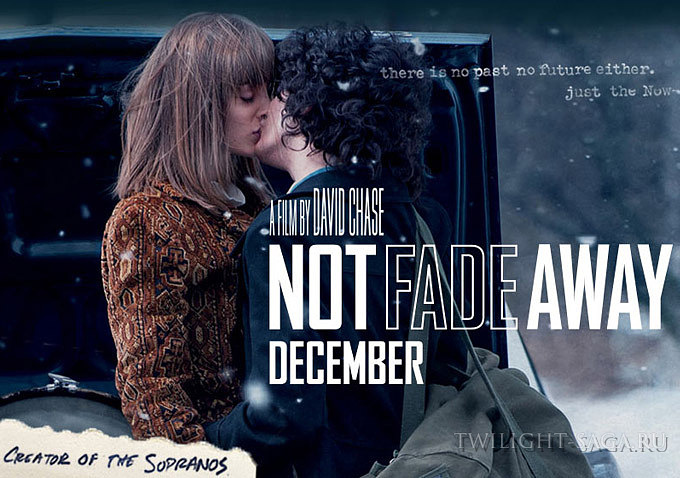

In the 70s George Lucas took us on a vivid, enthralling trip back to his 1962 -- the guys, the girls, the cars, the wall-to-wall music -- in American Graffiti. In the 90s Tom Hanks made his debut as a writer-director with That Thing You Do!, the relentlessly likable tale of a fledgling Erie, PA rock band. Now, in 2012, we have acclaimed veteran TV producer David Chase taking us back on a clearly autobiographical trip to the late 60‘s in Not Fade Away.

Chase, a seven-time Emmy award winner, is best known for creating the iconic, ground-breaking HBO series The Sopranos, but before deciding on film school, he played drums in a number of New Jersey bands in the 60s. Not Fade Away, about a drummer (John Magaro) in a struggling New Jersey band, is his feature writing-directing debut and it feels like something that’s been boiling inside of him for years, bursting to get out. Like many things that boil too long and finally burst or explode all over the place -- a volcano, for example -- the results are a mess.

Not Fade Away is all over the place, a hodgepodge of meandering sub-plots about not especially compelling or even sympathetic characters. With painstaking attention to period details and a pricey classic rock soundtrack, Chase seems not only preoccupied with recreating and reliving the precious 60s but more interested in revisiting, maybe even reinventing, his own past and less concerned with compelling, coherent storytelling. Every guy has the girl from their youth that they still can’t forget. I wonder how long the 60-something Chase spent looking for a 20-something actress to play the girl he never forgot.

Everyone can name a favorite song that came out when they were young, maybe even more than one. It can be easy to forget that for every song we loved when we were between sixteen and twenty, there were dozens of tunes that sucked and have been rightfully forgotten. Sometimes it is better to not hold onto everything. Maybe some things are better off fading away.

This review originally appeared on cinedelphia.com:

http://cinedelphia.com/not-fade-away-review

In the 70s George Lucas took us on a vivid, enthralling trip back to his 1962 -- the guys, the girls, the cars, the wall-to-wall music -- in American Graffiti. In the 90s Tom Hanks made his debut as a writer-director with That Thing You Do!, the relentlessly likable tale of a fledgling Erie, PA rock band. Now, in 2012, we have acclaimed veteran TV producer David Chase taking us back on a clearly autobiographical trip to the late 60‘s in Not Fade Away.

Chase, a seven-time Emmy award winner, is best known for creating the iconic, ground-breaking HBO series The Sopranos, but before deciding on film school, he played drums in a number of New Jersey bands in the 60s. Not Fade Away, about a drummer (John Magaro) in a struggling New Jersey band, is his feature writing-directing debut and it feels like something that’s been boiling inside of him for years, bursting to get out. Like many things that boil too long and finally burst or explode all over the place -- a volcano, for example -- the results are a mess.

Not Fade Away is all over the place, a hodgepodge of meandering sub-plots about not especially compelling or even sympathetic characters. With painstaking attention to period details and a pricey classic rock soundtrack, Chase seems not only preoccupied with recreating and reliving the precious 60s but more interested in revisiting, maybe even reinventing, his own past and less concerned with compelling, coherent storytelling. Every guy has the girl from their youth that they still can’t forget. I wonder how long the 60-something Chase spent looking for a 20-something actress to play the girl he never forgot.

Everyone can name a favorite song that came out when they were young, maybe even more than one. It can be easy to forget that for every song we loved when we were between sixteen and twenty, there were dozens of tunes that sucked and have been rightfully forgotten. Sometimes it is better to not hold onto everything. Maybe some things are better off fading away.

This review originally appeared on cinedelphia.com:

http://cinedelphia.com/not-fade-away-review

Sunday, December 23, 2012

"The Guilt Trip" aka "Rogen. Streisand. Man. Woman."

How would you like to see Bar Mitzvah Boys, starring Ben Stiller, Seth Rogen, Jack Black and Adam Sandler? That’s the question I ask my Introduction to Screenwriting students to gauge their reaction -- how many groan, how many say they plan to see it, how many groan and plan to see it, and how many of them think it will be a hit. Most of them want to see it and even those who don’t want to see it think it will be a hit. Next, I tell them that there is no such movie; that I made it up. That’s how the film industry works. That’s show business. “Hey, let’s put A-list Star 1 in a movie with A-list Star 2 and see how many people go see it.”

I can’t tell you exactly what went down with the development of The Guilt Trip, but I suspect that, somewhere down the line, there was a conversation that went, “Rogen. Streisand. Man. Woman. Mother. Son. Old Jew. Young Jew. Sounds like a movie to me!” And I suspect that the process of writing the screenplay was not much more sophisticated.

I cannot deny The Guilt Trip its charms. It has moments. I chuckled but ultimately I felt, for lack of a better word, guilty for allowing myself to enjoy it to even a small degree. It felt like I was rewarding mediocrity; like they got one over on me a la “I’m Seth Rogen and this is Barbra Streisand. We are going to banter onscreen for 90 minutes and you are going to love us.” I got suckered in; I sat there and watched this film that represented a minimal expenditure of creative effort. The Guilt Trip could have been better but I get the sense that nobody even tried to take it to the next level.

The first red flag for me was Rogen playing a subdued scientist. That’s just not right. Both Rogen’s performance and his character are inconsistent and not fully formed. In the drama Take This Waltz, Rogen shows that he can tone it down and play it straight but here, in a comedy, he feels stifled, as if he is not always sure of what he’s supposed to be doing with his character.

Streisand is a Jewish mother. That’s her character and that’s what she plays. Sure, even though they give her some backstory, her Joyce is not a real, dimensional woman with a personality, feelings and opinions; she is schtick. Jewish mothers are all the same. They don’t have personalities. They are Jewish mothers and that is their personality. That said, for all of her serious filmmaker moves in recent years, it is easy to forget that Streisand has genuine, comedic chops. Even though they were on display in the Focker movies, here she recalls her What’s Up, Doc and For Pete’s Sake era persona.

In the event that the onscreen pairing of Rogen and Streisand is not enough to send you racing to the nearest theater, there is a plot that involves, of all things, a man taking a cross-country trip with his mother. Rogen’s Andy is a sad-sack organic chemist who has invented an all natural organic cleaning product that is both safe to use and effective. His problem is that he is a terrible salesman and all of his pitches to major retailers fall flat. For some reason, he flies from his home in L.A. to his childhood home in New Jersey so that he can embark on a road trip to pitch the product. Believe me, I did see this movie but I swear I cannot remember or exactly figure out why he decides to invite his obnoxious, overbearing mother to join him. I write screenplays and teach screenwriting for a living and I am still trying to discern, understand and accept his motivation. That’s what I mean about taking this movie to the next level. I’m sure they could have come up with something better, couldn’t they?

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love road trip movies but does anyone ever take to the highways with someone they actually get along with? Oh, that’s right, movies are about people taking journeys --- either literal, physical trips or spiritual, emotional voyages -- where they end up in a new place, as new or whole, better, people. So, guess what, Andy and Joyce clash, things come to a head, they apologize, see each other in a new light, bond and move on, happier.

Guilt Trip 2: The Guiltier Trip, anyone?

This review originally appeared at Cinedelphia.

I can’t tell you exactly what went down with the development of The Guilt Trip, but I suspect that, somewhere down the line, there was a conversation that went, “Rogen. Streisand. Man. Woman. Mother. Son. Old Jew. Young Jew. Sounds like a movie to me!” And I suspect that the process of writing the screenplay was not much more sophisticated.

I cannot deny The Guilt Trip its charms. It has moments. I chuckled but ultimately I felt, for lack of a better word, guilty for allowing myself to enjoy it to even a small degree. It felt like I was rewarding mediocrity; like they got one over on me a la “I’m Seth Rogen and this is Barbra Streisand. We are going to banter onscreen for 90 minutes and you are going to love us.” I got suckered in; I sat there and watched this film that represented a minimal expenditure of creative effort. The Guilt Trip could have been better but I get the sense that nobody even tried to take it to the next level.

The first red flag for me was Rogen playing a subdued scientist. That’s just not right. Both Rogen’s performance and his character are inconsistent and not fully formed. In the drama Take This Waltz, Rogen shows that he can tone it down and play it straight but here, in a comedy, he feels stifled, as if he is not always sure of what he’s supposed to be doing with his character.

Streisand is a Jewish mother. That’s her character and that’s what she plays. Sure, even though they give her some backstory, her Joyce is not a real, dimensional woman with a personality, feelings and opinions; she is schtick. Jewish mothers are all the same. They don’t have personalities. They are Jewish mothers and that is their personality. That said, for all of her serious filmmaker moves in recent years, it is easy to forget that Streisand has genuine, comedic chops. Even though they were on display in the Focker movies, here she recalls her What’s Up, Doc and For Pete’s Sake era persona.

In the event that the onscreen pairing of Rogen and Streisand is not enough to send you racing to the nearest theater, there is a plot that involves, of all things, a man taking a cross-country trip with his mother. Rogen’s Andy is a sad-sack organic chemist who has invented an all natural organic cleaning product that is both safe to use and effective. His problem is that he is a terrible salesman and all of his pitches to major retailers fall flat. For some reason, he flies from his home in L.A. to his childhood home in New Jersey so that he can embark on a road trip to pitch the product. Believe me, I did see this movie but I swear I cannot remember or exactly figure out why he decides to invite his obnoxious, overbearing mother to join him. I write screenplays and teach screenwriting for a living and I am still trying to discern, understand and accept his motivation. That’s what I mean about taking this movie to the next level. I’m sure they could have come up with something better, couldn’t they?

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love road trip movies but does anyone ever take to the highways with someone they actually get along with? Oh, that’s right, movies are about people taking journeys --- either literal, physical trips or spiritual, emotional voyages -- where they end up in a new place, as new or whole, better, people. So, guess what, Andy and Joyce clash, things come to a head, they apologize, see each other in a new light, bond and move on, happier.

Guilt Trip 2: The Guiltier Trip, anyone?

This review originally appeared at Cinedelphia.

Monday, December 17, 2012

Sunday, December 16, 2012

Why I Do What I Do

I think I’ve finally made it. This week, one of my students started a Facebook group, Screenwriting 101 - Greeny Gone Wild, for former students of mine or anyone who is interested in what I might have to say about screenwriting.

Classes are over. The semester is history. At current count, I have read thirty screenplays and have thirty more to read by Monday. I am beat after fifteen weeks of lesson planning, lecturing and reviewing student work but now the end is in sight.

This week, a guy whom I taught two years ago asked me to read a feature length screenplay he wrote. As a break from grading, I read his work and returned it with extensive notes.

Then a couple of days ago, I heard from another former student, someone I had for two courses three or four years ago:

“You put forth dedication, heart and effort while looking over every one of your students' screenplays. I always appreciated that as a student of yours. This is why we keep in touch and I left that school knowing that I had ONE teacher that gave a shit.... you're the voice in the back in my head when I write anything from a press release to a 300 page EHR manual. 'Fewest best words.' You're incredible David Greenberg.”

When I finish grading student stuff, I get back to work on my own projects: a second draft of a documentary and an intensive rewrite of a screenplay by someone else.

I might not ever become a wildly successful screenwriter in the conventional sense and, at least once or twice a semester, I tell myself I can’t do it anymore. This is it. I’m done teaching. But every now and then, something comes along to remind me why I do what I do.

Classes are over. The semester is history. At current count, I have read thirty screenplays and have thirty more to read by Monday. I am beat after fifteen weeks of lesson planning, lecturing and reviewing student work but now the end is in sight.

This week, a guy whom I taught two years ago asked me to read a feature length screenplay he wrote. As a break from grading, I read his work and returned it with extensive notes.

Then a couple of days ago, I heard from another former student, someone I had for two courses three or four years ago:

“You put forth dedication, heart and effort while looking over every one of your students' screenplays. I always appreciated that as a student of yours. This is why we keep in touch and I left that school knowing that I had ONE teacher that gave a shit.... you're the voice in the back in my head when I write anything from a press release to a 300 page EHR manual. 'Fewest best words.' You're incredible David Greenberg.”

When I finish grading student stuff, I get back to work on my own projects: a second draft of a documentary and an intensive rewrite of a screenplay by someone else.

I might not ever become a wildly successful screenwriter in the conventional sense and, at least once or twice a semester, I tell myself I can’t do it anymore. This is it. I’m done teaching. But every now and then, something comes along to remind me why I do what I do.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Chasing Chase: How to Not Fade Away

On the last day of screenwriting class this semester, I asked my students if they had ever heard of Twin Peaks. If any of these students were even alive when it premiered in 1990, they would have been very young. Still, most of them had heard of the show and responded enthusiastically. Then I asked if they had ever heard of another series about the comings and goings of a variety of offbeat characters in a small, remote town, Northern Exposure, which also premiered in 1990. One student was vaguely familiar with it and not especially enthusiastic.

While I got caught up in the initial Twin Peaks mania, I began to feel that it was going nowhere fast.

It was a very cool idea for a show without really being about anything. By the

second season, the charm had worn off and watching became a chore. The writers seemed to be making things up as

they went along.

Northern Exposure did

not grab me from the start but I liked it, stuck with it and think that it

actually got much better as it went along. I believe the reason was that veteran producer David Chase was brought

in to oversee the show. Every episode felt like an offbeat but ultimately rich

and beautiful independent film. Maybe I was missing something there but, after

an episode of Twin Peaks, I could

usually say, “That was cool.” After an episode of Northern Exposure, I felt like I had something to think about and

discuss with others.

Chase started in TV as story editor in the seventies on one my

favorite shows, Kolchak: The Night Stalker,

but his career really took off when he became a producer on the well-regarded

hit show The Rockford Files. Chase created the

critically acclaimed but short-lived series I’ll

Fly Away before coming to work on Northern

Exposure. After Northern, Chase

created the HBO series, The Sopranos.

My students would have been little kids and young teenagers when the show ran.

Few, if any, had seen it, but when asked, most had heard of it.

To explain the significance of The Sopranos in the context of

episodic TV, I said to them, “Without The

Sopranos we would not have had The Wire, Breaking Bad, Sons Of Anarchy or American Horror Story, to

name a few.”

I saw David Chase’s feature film debut, Not Fade Away, the other night. Growing up in northern New Jersey

in the sixties, Chase was, like many kids in the Beatles era, pursuing rock and

roll dreams. He was a drummer in a number of bands before finally deciding to

go to film school. Not Fade Away is

about a young man in sixties north Jersey playing drums in a band and

eventually going to film school. I hated

the film not just because it was an incoherent mess but because its creator

fell into the same traps that so many other filmmakers have fallen into over

the years --- self-indulgently recreating, reliving and, to some degree,

re-inventing their past to make it interesting to themselves more than to an

audience. Based on nothing but instinct, I am guessing that, at one time, David

Chase had a relationship -- or wished he did -- with a girl who looks like the

female lead in his film. So much in this film must have been of great personal

significance to the filmmaker but winds up feeling empty and pointless to the

audience.

All of this stuff gets back to something that I bring up on the

first day of class every semester: the role of the artist in society. Artists

take in the world, observe and consider some piece of the human experience and

then represent (or RE-present) it in some form to an audience. In a best case

scenario, a work of art provokes the audience, stirring emotions and ideas.

Either the audience responds and relates to it or reacts against it. We all

have different experiences and we all have different tastes. Yes, you should draw

on personal experiences and feelings about things you have seen and done; they

should inform your work, but you have to remember to say something about the

world other than that it exists. The producers of Not Fade Away clearly took great pains to be extremely accurate

about period details. The problem is that we do not go to movies to see great

production design; we go to see good stories about interesting characters

working through circumstances that, in one way or another, we relate to, think

about, and take something away from, deriving a new sense of the world and our

place in it, whether we know it or not.

I tell my students on both the first and last days of class

that, as artists, they need to decide what they want to be and what kind of

work they want to do. They should be provocative; that is, create work that not

only entertains but also strikes a chord and makes people think or feel

something about the world around them, either on a small, intimate, personal

level or on a broader, grander scale.

They cannot -- well, they should not -- spoon feed the audience

simplistic, meaningless junk. I compare movies to food. There are health food

movies and there are junk food movies.

Their work should not just sit there like a bag of chips. Of

course, as I tell them, people like chips, and following that model, like junk

food movies. One can earn a pretty solid living making junk food.

All of the students in my class will be graduating in the next

year or two. One way or another, all of them want to make a living in the film

industry. Making art and making a living can be tough to combine.

I read a screenplay last week and I am getting paid to

evaluate it. The script was in really bad shape and I dreaded the idea of

talking to the writer, telling him how much I didn't like it. While I knew that

I couldn't tell him it sucks, I could point out what is wrong with it, what is

right with it and what it needs in order to be a good movie. I just got off of

the phone with the writer. He knows that it needs work and he was really

receptive to my ideas for it. I am very

likely to get hired to re-write the screenplay. I will find something in this story, something I can

work with, something that I can make entertaining and, if I am lucky, meaningful.

I will do my best on the job and, if I do my best, it just might wind up being

a pretty decent screenplay. So, do I put myself through this? Why am I going to

work so hard on it? Because this is what I want to do for a living.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)